Joel Thomas Hynes is not just blowing into New York, but taking his gritty stage performance to the Boston area too. Check out these posts for details. Nobody on the Eastern seaboard should miss this...

October 28, 2006 - Down to the Dirt in Cambridge.

September 23, 2006 - Down to the Dirt, unabridged audio edition.

Monday, October 30, 2006

Everything You Need to Know About Rattling Books in Iceland.

On October 31, Agnes Walsh and Anita Best head off to Iceland. For more information check out the following posts:

October 27, 2006 - Rattling Performances in Iceland

October 27, 2006 - Icelandic Poet Ingibjörg Haraldsdóttir to Judge Translation Contest

October 26, 2006 - Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldor Laxness, excerpt #5 (conclusion of this series).

October 22, 2006 - Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldor Laxness, excerpt #4.

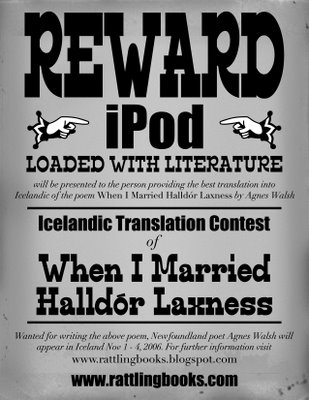

October 16, 2006 - Poster announcing an Icelandic Translation Contest of a Poem by Agnes Walsh

October 14, 2006 - Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldor Laxness, excerpt #3.

October 6, 2006 - Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldor Laxness, excerpt #2.

October 3, 2006 - Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldor Laxness, excerpt #1.

October 1, 2006 - What Readers Have Said About Mary Dalton's Merrybegot.

September 28, 2006 - Agnes Walsh and Anita Best to Perform in Iceland

September 26, 2006 - Full text of the Poem by Agnes Walsh When I Married Halldor Laxness .

October 27, 2006 - Rattling Performances in Iceland

October 27, 2006 - Icelandic Poet Ingibjörg Haraldsdóttir to Judge Translation Contest

October 26, 2006 - Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldor Laxness, excerpt #5 (conclusion of this series).

October 22, 2006 - Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldor Laxness, excerpt #4.

October 16, 2006 - Poster announcing an Icelandic Translation Contest of a Poem by Agnes Walsh

October 14, 2006 - Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldor Laxness, excerpt #3.

October 6, 2006 - Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldor Laxness, excerpt #2.

October 3, 2006 - Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldor Laxness, excerpt #1.

October 1, 2006 - What Readers Have Said About Mary Dalton's Merrybegot.

September 28, 2006 - Agnes Walsh and Anita Best to Perform in Iceland

September 26, 2006 - Full text of the Poem by Agnes Walsh When I Married Halldor Laxness .

Sunday, October 29, 2006

Don't Forget Our Hallowe'en Special on Dead Author Digital Downloads

HALLOWE'EN SPECIAL

DEAD AUTHOR DIGITAL DOWNLOADS

HALF ROTTEN - HALF PRICE!

DEAD AUTHOR DIGITAL DOWNLOADS

HALF ROTTEN - HALF PRICE!

between October 19 and November 1

only from www.rattlingbooks.com

Wilfred Grenfell (1865-1940) Adrift on an Ice PanDigital Download Reg $9.95 Hallowe'en Special $4.95

Captain Bob Bartlett (1875-1946) The Last Voyage of the KarlukDigital Download Reg $19.95 Hallowe'en Special $9.95

Dillon Wallace (1863-1939) The Lure of the Labrador WildDigital Download Reg $19.95 Hallowe'en Special $9.95

Saturday, October 28, 2006

From a Master to an Upstart - CanLit at the KGB Bar, NYC

On Friday, November 3, 2006, Rattling Books is pleased to present From a Master to an Upstart, an evening of performance at the KGB Bar in New York City.

Margot Dionne will read from Mavis Gallant's Montreal Stories, which has just been released as an audiobook by Rattling Books. She will be joined in performance by Newfoundland's own Joel Thomas Hynes, who will read from his acclaimed novel Down to the Dirt.

Come hear the evolution of Canadian literature, before your very ears.

Friday, November 3, 2006.

The KGB Bar, 85 E. 4th Street, 2nd Floor, NYC.

7:00 pm.

Down to the Dirt in Cambridge

Rattling Books is pleased to announce the Boston launch of Joel Thomas Hynes' Down to the Dirt.

On Sunday, November 5, 2006, Joel will be performing at The Middle East in Cambridge.

Did we mention there's belly dancing, too?

We'll see you there... Sunday, November 5, 2006. The Middle East, 480 Massachusetts Drive, Cambridge, MA. 8:00 pm.

Mavis Gallant Tribute at Symphony Space in NY is the Time Out NY Top Pick of the Week

On November 1, authors Russell Banks, Jhumpa Lahiri, Michael Ondaatje and Edward Hirsch will join legend Mavis Gallant at the Symphony Space in New York for a tribute to her life and work.

This is a rare event-- to see Mavis Gallant and hear her read her stories. Time Out NY thought so, too. They've chosen the Mavis Gallant tribute as their not-to-be-missed event of the week.

Rattling Books will be there with our copies of Montreal Stories hot off the presses. We are overjoyed and honored to publish Mavis Gallant and we can't wait for next Wednesday.

Drop by and say hello.

Excerpt from a Work in Progress Excerpt from Author Susan Rendell

Susan Rendell has got the disease. She's got Writing. She's pathological. She can't stop herself from spewing syllables, testing text, knitting notes and for all we know when she's holed up in bed she's fucking fonts.

Susan Rendell is the author of In the Chambers of the Sea, a collection of short fiction released as an audio edition by Rattling Books in 2004. The fourteen stories in the collection are narrated by Anita Best, Deirdre Gillard-Rowlings, Joel Hynes, Susan Rendell, Janet Russell, Janis Spence, Francesca Swann and Agnes Walsh. This coming week two of those narrators (Agnes Walsh and Anita Best) are performing in Iceland and among other things will read from In the Chambers of the Sea.

Here is an excerpt from one of the substances Susan Rendell is excreting lately. She says it's an historical novel (but given her other condition, wit, it may also be an hysterical novel).

Adelaide Taylor Godfrey

When Sandy came back from the War he brought pictures of himself with whip-thin Italian orphans hanging off his shoulders like monkeys. Twenty-five, he was; three years out of medical school and all of them spent at the War, trying to put the broken soldiers back together.

One time at the Dalhousie medical school a staff man threw a woman’s leg at him after an operation. He caught it the way he used to catch his sisters jumping down from the hay loft, and bringing his face close to the gangrenous toes, he asked it to be his bride. “But she wouldn’t have me, Mother, no sir; she said I was too big for my britches. Or maybe she said she was too big for my britches, I can’t remember exactly.”

Beside the silver-circled wedding picture over the big sleigh bed, there’s a picture of Sandy in an oak frame with a crack in it; the crack is beside his right ear, the one that got frostbitten so bad the winter he was ten they thought it was going to drop off. He and six other doctors are standing around a roadster in front of the Victoria General wearing white coats. Stethoscopes curl around their necks like tame garter snakes; perhaps the car needs a check-up.

On the mahogany sideboard haughty with Wedgwood plates and Limoges demitasse cups so delicate you can almost see the light from the bow window shivering through them, Sandy and his mother are standing on the platform of the train station a mile from the shaggy old house, inside an ivory oval. He’s wearing an officer’s uniform and holding his walking stick in the air, pretending it’s a baton, that he’s conducting the people coming off the train so they won’t bump into one another. His mother’s head comes up to his shoulder; the long feather stuck in her flat black cow pie hat reaches up to tickle his ear. She’s holding onto his arm with both her hands and smiling as if he’s a prize she has just won in the church raffle.

Two weeks after Sandy got home the coughing started. She sat up with him until dawn the first night. He hung onto her arm and spit up gobs of yellow saliva with red veins into a chamber pot with asters on it. He once told her they put asters on the graves of the French soldiers. For regret, not remembrance, he said.

“Never mind,” she said, tugging on his thick hair. She used to have hair like that, hair the colour of a gold finch and coarse as rope. On her wedding night Sandy’s father wrapped it around his throat before he went to sleep. Watch you don’t get a rash from that, she said. It’s pricklier than a stinger nettle. She always considered this her first utterance as a wife; there was such an ordinariness in the way she said it, as if a man going to sleep in her bed with her hair around his throat was the most natural thing in the world.

“We’ll send you to the San; it’s only bad food and working around the clock that’s got you like this. But you’re young and strong—I nursed you for nearly a year, did you know that? Yes, I did, the girls only got six months of me between them, but I let you go on as long as you pleased. Anyway, no Godfrey ever died before his eightieth birthday.”

They buried him nine months later, in an oak casket with a Union Jack spread across it. She started to go back to the house, to get the crazy quilt off his spool bed, to take the flag off and tuck him up in the quilt, with its blood stains sunk into the border roses. You couldn’t tell it was blood unless you’d been there watching it leak out into those silk roses night after night, wishing it was your blood. But her husband had hold of two of her black-gloved fingers as if they were the teats of a stubborn cow.

It hadn’t been tuberculosis after all. The mustard gas creeping from the pockets of the uniforms of his patients had killed her son. The dirty Hun gas, leaching into her son’s lungs out of the rags wrapped around the ruined young men plucked out of the French mud like half-dead flowers. The flower of a generation they said, and so they were. And her Sandy had been the pick of the Queen’s County crop. Dr. Miller’s daughter never married, never even walked out with another man afterwards.

Their eyes, he said to his mother one night between spasms – a real bad night, he’d been tearing at the quilt like a woman in labour - were as blind as the eyes of the dead calves Father and I used to butcher. Blind and blistered and dying, suffocating and fighting it, desperate to make their lungs work, only they were nothing more than tattered bellows. There was a certain sound. . .you knew when you heard it the chap was a goner. We had to strap most of them to their beds in the end. One night I pushed a pillow down over a fellow’s face. What was left of it. Do you think that was murder? No, said his mother, winding the fine hairs at the back of his neck around her finger. I think it was mercy.

When he was little, she used to make him big veal sandwiches with mustard pickles from the root cellar, and they would hitch Black Prince to the buggy and go to the sea, the two girls and her husband and Alexander, her only son, born a year to the day after Doctor Miller told her she was past having any more children. On the cherry wood table beneath the Currier and Ives of Havana Harbour one of Cousin Margaret’s lovers gave her, there’s a photograph of him at eight years, standing up to his knees in the sand at Eagle Head. Sandy Sandy she wrote on the back of it, using her father’s goose quill pen and the last packet of powdered ink in the house.

Now when she makes sandwiches for her husband and he says, Addie, where are the mustard pickles, she tells him the cucumbers didn’t come up this year. That they stayed in the ground. That she doesn’t expect to see them again until the Resurrection Day.

Friday, October 27, 2006

Rattling Performances in Iceland

Rattling Books is pleased to announce that Agnes Walsh and Anita Best will be performing at the following venues in Iceland from November 1 - 4, 2006.

Wednesday, November 1, 2006 – The Nordic House, Sturlugata 5, 101 Reykjavík, at 20:00.

Friday, November 3, 2006 - Samtokin '78 - Regnbogasalur (Rainbow Room), Laugarvegur 3 - 4th floor, 105 Reykjavik, at 20:30.

Saturday, November 4, 2006 - Gljúfrasteinn Museum, the home of Nobel winning Icelandic author Halldor Laxness, Gljúfrasteinn, 270 Mosfellsbær, at 12:00.

Agnes and Anita are thrilled to finally bring Agnes' work full circle. The translation of her poem When I Married Halldor Laxness into Icelandic and the performance in Laxness' home means this will be an exciting week for everyone. Check it out!

Icelandic Poet Ingibjörg Haraldsdóttir to Judge Translation Contest

Rattling Books is pleased and honoured to announce that Ingibjörg Haraldsdóttir, one of Iceland's most accomplished poets and outstanding translators, will be judging our translation contest.

The winning translation into Icelandic of Agnes Walsh's When I Married Halldor Laxness will be announced on Wednesday, November 1, at the Nordic House. The winning translator will read their translation in performance with Agnes Walsh and Anita Best.

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldór Laxness, Final Excerpt from an essay by Stan Dragland

The following is the fifth and final installment in a series of excerpts from an essay by Stan Dragland (and conversation between Stan (SD) and Agnes Walsh (AW)) published in Brick 68 (Fall 2001). Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldór Laxness (continued from October 22). Agnes Walsh is the author of In the Old Country of My Heart which she recorded for Rattling Books in 2003. Between October 31 and Nov 4 Walsh will be appearing in Iceland with traditional Newfoundland singer and narrator Anita Best.

Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldór Laxness (continued from October 22)

AW:

After the reading of “When I Married Halldór Laxness” Stan asks “What does all this mean?” And now I suppose I could ask the same of his writing about my poem. What does it all mean to have your work poked at like that? Well, the first reaction would be flattery, sure, since he has said nothing bad about it. He has paid attention and thought it worthwhile to get in under the skin of the poem and check out the blood-flow, so to speak.

I have never thought of myself as an intellectual yet I do not consider myself a slouch in the world of ideas either. In the same way that I couldn’t “take” to classical music much in my life but rather got interested in black jazz (I mean free-form jazz) early on, so I liken my literary pursuits to jazz over classical training. I quit school at the end of Grade 9 because I was bored. I was learning nothing there and plenty by reading on my own books supplied to me by an American sailor who worked for Naval Intelligence in Argentia, himself a high school drop-out from Brooklyn.

What I’m trying to get at here is that I do not analyze classically/intellectually but can appreciate work that comes from those who do. My reading has always been all over the place but my writing pretty much stems from here, from this place, even when I go as far afield as Iceland, or say Portugal.

Stan and I met through literature and folktale. He asked about a play I worked in entitled Jack Meets the Cat, based on a folktale from Pius Power Sr. of Southeast Bight, Placentia Bay. Stan liked the cassette of this play. He liked it a lot and I always loved working on it. When Stan and his family moved here I watched how he became part of life here. Not just literary life but part of the landscape, the rhythms, the people. He never seemed like an outsider to me and I can be touchy about that. To people from away and how they see us. When he told me what he was up to with writing this piece I was especially pleased that he picked this poem. I’ve always loved this poem, if I can say that about my own work. For me it is as clear as a bell about my feeling of connectedness to place, to writing, to love, to sex. Stan seemed to understand my writing from “inside a saga” that is literature and that is connectedness to place. He also seemed to understand my falling for a writer’s work and how it was ok to gush love for Laxness and write about marrying him. I know that great writers’ works can change your life. If not, I’d never have left Placentia, and leaving was essential to my life as a writer. Leaving and returning.

I see that Stan recognizes in Newfoundland a uniqueness that is worth checking out. I think my work is a small part of what Stan is interested in here. In the same way that I thrilled at reading about Newfoundland in a Danish novel translated into English so I do thrill at someone taking an interest in my work. Laxness paid tribute to the writers of the sagas believing that without their legacy Iceland would have remained just another Danish island. I come nowhere close to saga or Laxness size but my drop in the bucket of writing in Newfoundland is, I believe, important to a sense of self and place for us here. I read no Newfoundland writers growing up, let alone a Newfoundland saga. I thought you had to be British to write. I thought you had to be high-brow to have anything worth saying. I thought like that because of the ignorance of the educational system that I left behind me. It was only on my return that I discovered folktale and that I had relations composing ballads that are still sung today.

Stan paying attention reinforces that sense of pride of place. It is more than an ego boost. I read a lot of literary biographies and studies of writers’ works, critiques of poems of, say for instance Elizabeth Bishop, by academics and writers who want to know how her life influenced her writing and some is very helpful and some is downright silly. I had a professor once write about line in a poem of mine. The line was about children pencilling beards on Queen Elizabeth. The professor wrote that it was a show of cross-gender, homo-erotic child play. Well, I don’t mind that, and she could be correct but I saw it more as a show of “up the monarchy.” Who’s to say who’s right? Really, the writer is only half right because life, and especially the creative process, is never so simple as we alone see it.

I think Stan is right that the poem is a story. I hope the story is a poem too.

SD:

When Agnes and I were done, there were a few questions and comments. One of the comments was oblique to our presentation. It was a typical rumination about the love-hate ambivalence felt by many Newfoundlanders for their place. To lift the heart, there’s the intricate elemental landwash and layers of distinctive culture; to make it plummet there’s the have-not economy, with notorious giveaways by Newfoundlanders themselves, and heartrending out-migration. Fierce pride and low self-esteem. A compact, cynical variation on this bind appears in William Rowe's novel, Clapp's Rock, when Percy Clapp, a Joey Smallwood figure, speaks of

that bizarre form of pride of place possessed in embryo by all poor and isolated peoples (don’t ask me why -- it defies reason -- I only use the materials at hand), the belief that they are in some paradoxical way better than all the other peoples and countries to which they feel inferior.

Somewhere behind such ruminations is almost always the humiliating 1933 resignation of Newfoundland’s responsible government by a country honourably bankrupt but badly run, followed by over a decade of colonial rule and then, in 1948, confirmation of subordinate status by absorption into another nation. Only to become a national joke. Many Newfoundlanders, Agnes Walsh among them, have understandably never become Canadians, not in spirit. There is a Newfoundland nation, but nobody can have it.

Not much a CFA (Come From Away) can say about such affliction other than to commiserate. And watch for signs of healing humour. There is a Newfoundland branch of subversive minority humour, and one fork of the branch is a sophisticated and eloquent self-disparagement, a far cry from the patronizing Newfie joke, that outsiders attempt at their peril. After the formal session, the ruminator told a joke on Newfoundlanders that I´d have too much sense to repeat even if I could remember it.

During the question period another man had tried in various ways to ask me something that I wasn’t getting, so, one-to-one, I asked him to try again. It turned out that he was wondering about identity, about the status of CFAs like ourselves who aren’t absorbed by the culture. "It's not love and hate for me,” remarked another man, a historian from the U.S. with thirty years of residence in St. John’s, "it’s love and bewilderment.” My questioner was an Engineering professor of about the historian’s vintage, but from Denmark. Both were sharing this slightly bemusing, not-disagreeable sense of arm’s-length residence, this conviction that it’s preferable to live here in a mild sort of exile than to be anywhere else. I suppose the engineer was wondering what I’d have to say on the subject since Agnes had endorsed me as one who “became part of life here.” I was touched by that, though it wasn’t the sort of literary observation I’d invited. I wasn’t looking for compliments. In any case, I was surprised to feel the endorsement actually push me further out. I told the engineer that I sometimes feel a sort of panic here, wondering what foolishness induced me to commit to a society whose patterns and assumptions I’ll never intimately understand.

Well, Ugla of Eystridaldur, the heroine of Halldór Laxness’s The Atom Station, has this to say as she prepares to return to Reykjavík from her home in northern Iceland: “I had long begun to count the days until I could once again leave home, where I felt an alien, and go out into the alien world, where I was at home.” “Where do you come from?” That’s a standard question in most of Canada. In Newfoundland it’s more likely to be “Where do you belong?” A much tougher question, enough to lift you off whatever patch of the very earth you’re standing on. Where do I belong? Alberta, no question. But I won’t be going back there except to visit.

Still turning all this over a few days later, I arrived at the obvious: identity can’t be conferred. A stickler like Agnes approves of my way of checking Newfoundland out? Good, that’s a plus, I’m encouraged to keep at it. But looking at these good, open-minded, attention-paying men, the historian and the engineer, I see myself a quarter of a century hence, a lot more rickety but still loving and bewildered, fascinated and pissed off -- torn like a true Newfoundlander, yes, but for different and distancing reasons. The best I can hope is that the years turn me into an oyster. You know -- alien grit invades my shell and torments me to surround it with the best of myself.

The End of this 5 part series.

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

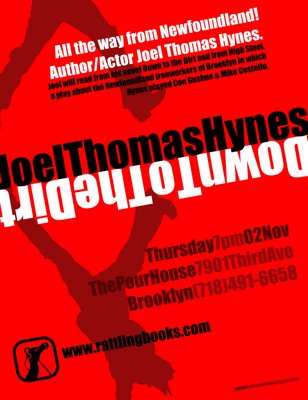

Joel Thomas Hynes to read for Newfoundland Ironworkers in Brooklyn

Joel Thomas Hynes will appear at the Pour House in Brooklyn to give a reading from his novel Down to the Dirt and the play High Steel about the Newfoundland ironworkers of New York, most of whom lived and continue to live in Brooklyn where they are known as "Fish".

If you happen to be in Brooklyn on Nov 2 head down to the Pour House 7901 Third Ave. Brooklyn, Phone: (718) 491-6658. The Pour House is owned and operated by Billy Quinlan who is the son of retired iron worker Willy Quinlan from Holyrood, Newfoundland and Jimmy Whiffen whose grandparents came from St. John's, Newfoundland.

Rattling Books would like to thank Danny Doyle and Bob Walsh of the Iron Workers Local 40 for helping to arrange this Reading. We would also like to thank Billy and Willy Quinlan for arranging the venue.

Down to the Dirt, Joel's first novel was released as an unabridged audio book by Rattling Books in 2006. It is read by Joel Thomas Hynes, Sherry White and Jonny Harris. Read more about the audio release of Down to the Dirt on an earlier post to this Blog.

High Steel was written by Mary Walsh and Rick Boland in the 1980s and recently remounted in St. John's with Joel Thomas Hynes playing Con Gushue and Mike Costello.

Read more about the High Steel musical saga in the Independent.

Rattling Books Buttons

We can't decide who is cuter, our logo or Joel Thomas Hynes when he's upside down. Either way we figure they're both cute as a button so we're getting in to the craze.

Order Joel's Down to the Dirt MP3 CD now from Rattling Books and we'll send you his iconic cartwheel to pin on your blazer.

Tuesday, October 24, 2006

Who Is Brian O’Dea Anyway?

The man behind the Fresh Fish Award for Emerging Writers in Newfoundland and Labrador is not your average arts patron. He’s not your average author, either.

He orchestrated two of the largest drug hauls in U.S. history and he hails from St. John’s, Newfoundland. You can read all about it in his book: High: Confessions of a Pot Smuggler.

Truth is stranger than fiction.

He orchestrated two of the largest drug hauls in U.S. history and he hails from St. John’s, Newfoundland. You can read all about it in his book: High: Confessions of a Pot Smuggler.

Truth is stranger than fiction.

Writers' Alliance of Newfoundland and Labrador Announces Winner of Fresh Fish Award

This weekend, the Writers’ Alliance of Newfoundland and Labrador held their annual conference once again at the Masonic Temple in St. John’s. The event brings together

writers from all over the province for a weekend of literary frolicking, creative workshops, and a banquet where everyone dons costumes and celebrates another year of

spectacular literature from this easternmost region of North America.

This year added a new event to the mix: The announcement of the Fresh Fish Award for Emerging Writers. This award is generously sponsored by Newfoundland author Brian O'Dea and provides one of the most generous cash prizes in Canada for an unpublished writer. The winning author receives a cash prize of $4,000, in addition to editing services of a professional editor valued at up to $1,000 and her or his name inscribed on a brass plaque, and a miniature sculpture in the style of "Man Nailed to a Fish" by sculptor Jim Maunder. The two runners-up each receives $1,000 cash.

In his speech, Brian remarked that his bank account isn’t large by any means, but he wanted to give back to the community and encourage emerging writers in his home province, adding that anyone else who would like to follow in his footsteps is more than welcome. Here, here Brian.

Congratulations to Sara Tilley (Snowflake-Young), the winner of the inaugural Fresh Fish Award. Sarah chose to read a selection from her manuscript that was set in the Masonic Temple and I swear by the time she finished her characters were shuffling through the hallways and arguing in the coatroom.

Congratulations also to the two finalists Claire Wilkshire (Maxine) and Degan Davis (The Forgetting Room).

www.rattlingbooks.com

writers from all over the province for a weekend of literary frolicking, creative workshops, and a banquet where everyone dons costumes and celebrates another year of

spectacular literature from this easternmost region of North America.

This year added a new event to the mix: The announcement of the Fresh Fish Award for Emerging Writers. This award is generously sponsored by Newfoundland author Brian O'Dea and provides one of the most generous cash prizes in Canada for an unpublished writer. The winning author receives a cash prize of $4,000, in addition to editing services of a professional editor valued at up to $1,000 and her or his name inscribed on a brass plaque, and a miniature sculpture in the style of "Man Nailed to a Fish" by sculptor Jim Maunder. The two runners-up each receives $1,000 cash.

In his speech, Brian remarked that his bank account isn’t large by any means, but he wanted to give back to the community and encourage emerging writers in his home province, adding that anyone else who would like to follow in his footsteps is more than welcome. Here, here Brian.

Congratulations to Sara Tilley (Snowflake-Young), the winner of the inaugural Fresh Fish Award. Sarah chose to read a selection from her manuscript that was set in the Masonic Temple and I swear by the time she finished her characters were shuffling through the hallways and arguing in the coatroom.

Congratulations also to the two finalists Claire Wilkshire (Maxine) and Degan Davis (The Forgetting Room).

www.rattlingbooks.com

Sunday, October 22, 2006

Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldór Laxness, Excerpt #4 from an essay by Stan Dragland

The following is the fourth in a series of excerpts from an essay by Stan Dragland (and conversation between Stan (SD) and Agnes Walsh (AW)) published in Brick 68 (Fall 2001). Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldór Laxness (continued from October 14).

Agnes Walsh is the author of In the Old Country of My Heart which she recorded for Rattling Books in 2003. Between October 31 and Nov 4 Walsh will be appearing in Iceland with traditional Newfoundland singer and narrator Anita Best.

SD (from “Dreaming Backwards: the Poetry of Agnes Walsh”):

What does all this mean? I always hear that question in the voice of the bewildered witness to a metaphysical gunfight in Ed Dorn’s Gunslinger. The gun “occurs” in the Slinger’s hand and with it he “describes” his opponent:

What does the foregoing mean?

I asked. Mean?

My gunslinger laughed

Mean?

Questioner, you got some strange

obsessions, you want to know

what something means after you’ve

seen it, after you’ve been there

or were you out during

that time?

The gunslinger is nothing if not hip. He’s a hip intellectual cowboy demi-god, so he isn’t going to be down on interpretation. I think the person who wrote him is saddling “I” with the common paralysis of a mind stormed with experience not immediately intelligible. Jesus, Slinger might say, is that all you can think to ask? That is the first thing you want to know? You can’t just go with it for a spell? You want a fucking paraphrase?

Well, it doesn’t really do to sneer at the uncomprehending, seeing that it’s you and I. And we do want to know. We’d rather understand than be hip. We might begin by improving the question. What’s going on in the above? Let’s ask that. It frees us right away to think about genre and technique.

First, a catalogue of the obvious -- which immediately changes the genre, from poem into story. “When I Married Halldór Laxness” looks like a poem (and Agnes thinks of it as such; prose poem -- no line breaks) because the narrative is so stark, but the piece has narration and dialogue and the bones of a plot. At the centre of the plot (so reduced as to be almost all centre) is a January-May pair of characters, first attracted but at odds, who move closer to each other in the course of the story. The time scheme is linear. It spans seven years of the relationship. After the first scene, we jump into the next night, then to the next week, then two years later, five years later. The final scene is the first one given in the present tense; that shift in tense reveals a present from which the rest of the (past tense) tale is retrospectively told.

The most dreamlike least developed aspect of narrative technique is setting. When the woman spills beer on the pant leg of a man, she presumably does it in a room. The room is in her house, presumably, since he’s the one who leaves. The phone, the doorbell, the door: these bare details also imply a house. Seven years later, a house (the same one?) is implied by its back yard. And that’s it. “Glacier is in Iceland” gives no clue as to where the house might be, since the woman has been fooled into thinking she can reach it from where she lives, which may be but is not identifiable as Newfoundland. (Glacier is not in Iceland, not on the map anyway -- though glaciers are; rather, it’s a fictional place in Laxness’s allegorical novel, Christianity in Glacier). Nor is the parenthesis (containing a scene from the aftermath of the 1929 Newfoundland tidal wave) locational, since that woman in the dislodged floating house has no obvious connection with the two characters. This two-sentence parenthetical unit has as much setting as the rest of the piece, however: a house, a bay, a town -- St. Lawrence near the tip of the Burin Peninsula.

The narrator is a young(ish?) woman involved in a strange, arbitrary relationship with an older man, perhaps even an aged man who yet has the potency to father children -- though in a manner comic and more of myth than biology (the third pregnancy is caused by a laugh). The story opens at a moment of crisis, of decision. Tension between the two characters is established by a bit of aggressive play with a glass of beer. He has most of the speech. She sighs once, but otherwise speaks only two words, “Yes” and “No.” Reticence aside, she is not passive. She is unapologetic about spilling beer on him; she decides immediately to “hang in this ether land,” though she knows the decision will cost her; she refuses to look at him when he commands her to. (He seems to be raising obstacles, testing her. Will your decision stand if you know in advance that I’ll mistreat you, and unpredictably?) Yet she is obsessed with him. She attempts to find the impossible rendezvous he appoints; she has a lover’s reaction to the gift of Aksel Sandemose books, matching her fingers to his prints on it. None of the riddling deters her; she doesn’t give up on him.

The turning point, the moment of mutual commitment, seems to come in the section beginning “two years later.” Two sentences carry the bones of a (marriage?) ceremony, perhaps involving a candle. There is a match in her trembling hand, and she may be lighting the candle that signals her readiness. (Only adjacency connects this candle with the one carried from window to window of the floating house.) Possibly she is now repeating the “Yes” she offered two years ago, though it would be stretching to identify readiness to “hang in this ether land” with readiness to marry. The adverb “shyly,” though strange modifying “crippled” (a verb here, usually a noun) suggests a change in him, a mellowing.

Five years later, the two of them are (still?) together, if we can go by the babies and his back yard chopping, signs of domestic arrangement. His conversation is as enigmatic as ever. Since he’s clearly the guy for her, she must absolutely love non sequitur. He still demands her attention, her gaze at least, and he reminds her (as the story flashes back) of a command that he now reveals to have been a joke: he lured her to a rendezvous that he made sure she couldn’t locate. Were those torn-out pages from a guide book or a novel? Is that “ether land” fiction? If I didn’t know Walsh to be a devoted reader of Halldór Laxness, would it occur to me to wonder if the marriage has to do with the relationship between fiction and a loving reader?

*

If the foregoing has any use it’s to show that conventional literary analysis will get us somewhere with “When I Married Halldór Laxness.” The terms that work best were shaped to discuss fiction, which means either that what I first took to be a poem should be reclassified as a story or that, at a certain degree of truncation, story becomes poem.

Agnes Walsh is the author of In the Old Country of My Heart which she recorded for Rattling Books in 2003. Between October 31 and Nov 4 Walsh will be appearing in Iceland with traditional Newfoundland singer and narrator Anita Best.

SD (from “Dreaming Backwards: the Poetry of Agnes Walsh”):

What does all this mean? I always hear that question in the voice of the bewildered witness to a metaphysical gunfight in Ed Dorn’s Gunslinger. The gun “occurs” in the Slinger’s hand and with it he “describes” his opponent:

What does the foregoing mean?

I asked. Mean?

My gunslinger laughed

Mean?

Questioner, you got some strange

obsessions, you want to know

what something means after you’ve

seen it, after you’ve been there

or were you out during

that time?

The gunslinger is nothing if not hip. He’s a hip intellectual cowboy demi-god, so he isn’t going to be down on interpretation. I think the person who wrote him is saddling “I” with the common paralysis of a mind stormed with experience not immediately intelligible. Jesus, Slinger might say, is that all you can think to ask? That is the first thing you want to know? You can’t just go with it for a spell? You want a fucking paraphrase?

Well, it doesn’t really do to sneer at the uncomprehending, seeing that it’s you and I. And we do want to know. We’d rather understand than be hip. We might begin by improving the question. What’s going on in the above? Let’s ask that. It frees us right away to think about genre and technique.

First, a catalogue of the obvious -- which immediately changes the genre, from poem into story. “When I Married Halldór Laxness” looks like a poem (and Agnes thinks of it as such; prose poem -- no line breaks) because the narrative is so stark, but the piece has narration and dialogue and the bones of a plot. At the centre of the plot (so reduced as to be almost all centre) is a January-May pair of characters, first attracted but at odds, who move closer to each other in the course of the story. The time scheme is linear. It spans seven years of the relationship. After the first scene, we jump into the next night, then to the next week, then two years later, five years later. The final scene is the first one given in the present tense; that shift in tense reveals a present from which the rest of the (past tense) tale is retrospectively told.

The most dreamlike least developed aspect of narrative technique is setting. When the woman spills beer on the pant leg of a man, she presumably does it in a room. The room is in her house, presumably, since he’s the one who leaves. The phone, the doorbell, the door: these bare details also imply a house. Seven years later, a house (the same one?) is implied by its back yard. And that’s it. “Glacier is in Iceland” gives no clue as to where the house might be, since the woman has been fooled into thinking she can reach it from where she lives, which may be but is not identifiable as Newfoundland. (Glacier is not in Iceland, not on the map anyway -- though glaciers are; rather, it’s a fictional place in Laxness’s allegorical novel, Christianity in Glacier). Nor is the parenthesis (containing a scene from the aftermath of the 1929 Newfoundland tidal wave) locational, since that woman in the dislodged floating house has no obvious connection with the two characters. This two-sentence parenthetical unit has as much setting as the rest of the piece, however: a house, a bay, a town -- St. Lawrence near the tip of the Burin Peninsula.

The narrator is a young(ish?) woman involved in a strange, arbitrary relationship with an older man, perhaps even an aged man who yet has the potency to father children -- though in a manner comic and more of myth than biology (the third pregnancy is caused by a laugh). The story opens at a moment of crisis, of decision. Tension between the two characters is established by a bit of aggressive play with a glass of beer. He has most of the speech. She sighs once, but otherwise speaks only two words, “Yes” and “No.” Reticence aside, she is not passive. She is unapologetic about spilling beer on him; she decides immediately to “hang in this ether land,” though she knows the decision will cost her; she refuses to look at him when he commands her to. (He seems to be raising obstacles, testing her. Will your decision stand if you know in advance that I’ll mistreat you, and unpredictably?) Yet she is obsessed with him. She attempts to find the impossible rendezvous he appoints; she has a lover’s reaction to the gift of Aksel Sandemose books, matching her fingers to his prints on it. None of the riddling deters her; she doesn’t give up on him.

The turning point, the moment of mutual commitment, seems to come in the section beginning “two years later.” Two sentences carry the bones of a (marriage?) ceremony, perhaps involving a candle. There is a match in her trembling hand, and she may be lighting the candle that signals her readiness. (Only adjacency connects this candle with the one carried from window to window of the floating house.) Possibly she is now repeating the “Yes” she offered two years ago, though it would be stretching to identify readiness to “hang in this ether land” with readiness to marry. The adverb “shyly,” though strange modifying “crippled” (a verb here, usually a noun) suggests a change in him, a mellowing.

Five years later, the two of them are (still?) together, if we can go by the babies and his back yard chopping, signs of domestic arrangement. His conversation is as enigmatic as ever. Since he’s clearly the guy for her, she must absolutely love non sequitur. He still demands her attention, her gaze at least, and he reminds her (as the story flashes back) of a command that he now reveals to have been a joke: he lured her to a rendezvous that he made sure she couldn’t locate. Were those torn-out pages from a guide book or a novel? Is that “ether land” fiction? If I didn’t know Walsh to be a devoted reader of Halldór Laxness, would it occur to me to wonder if the marriage has to do with the relationship between fiction and a loving reader?

In a tale so curtailed, little becomes much. Climax and dénouement require a single sentence. “Gentle laugh,” added to “shyly,” suggests either that he has mellowed or that all his earlier threats were a front to discourage too easy involvement in an inappropriate and bumpy relationship. A few facts can be established about the story, then, but I’ve had to be very tentative and ask a lot of questions. There are further questions: Abstract and Zero? These are likely names for babies neither in real life (with apologies to Zero Mostel) nor in any fiction with pretensions to realism. The names do frame the whole gamut of alphabet, A to Z, and they might tease certain minds towards philosophy and mathematics. Didymus? The Greek name (‘twin’) of St. Thomas, the doubter who needed and received physical evidence of Christ’s resurrection. “Under my fingernails?” Some things will have to be left hanging in the ether. But then I don’t expect the piece to mean piecemeal. The whole thing is dreamlike, riddling, nonsensical. It teeters on an edge between the ominous and the humorous. In it there is this sense of an independent woman prepared to sacrifice something in order to remain in a (metaphorical) land presided over by an unintelligible but compelling man with the almost godlike power of creating life by laughing.

*

If the foregoing has any use it’s to show that conventional literary analysis will get us somewhere with “When I Married Halldór Laxness.” The terms that work best were shaped to discuss fiction, which means either that what I first took to be a poem should be reclassified as a story or that, at a certain degree of truncation, story becomes poem.

All that’s missing from what I’ve said so far is everything, the spirit of the piece. Or am I nearing it with my hunch that the dreamlike story is a transmutation of Agnes’s relationship with Laxness’s books? That impregnating laugh, for instance: mythic, yes, and with the feel of heroic Laxnessian hyperbole. From The Atom Station: “And Geiri of Midhouses laughed -- that laugh that would suffice to build a cathedral, even on the summit of Mount Hekla.”

One of Mario’s Ruoppolo’s questions for Pablo Neruda is left unanswered in the film, Il Postino: “The whole world is a metaphor for something else?” Neruda takes the question seriously, but he wants to sleep on it and I can see why. Life in the film moves on and the question never comes up again. I wonder if a similar question should be asked of “When I Married Halldór Laxness,” since it’s both compelling and enigmatic from one end to the other: is the poem a metaphor for something else in its entirety? I think there’s a roundabout way of answering by way of material that might even have been presented first except that it fell beyond the reach of unaided interpretation. Only when my own thinking and researching is exhausted would I consider asking the writer anything about her text. I don’t want any approach foreclosed by deference to the writer. A critic in the pocket of a writer is a puppet or a parrot -- though a critic with nothing to offer the writer should find some other line of work. But it would be silly to ignore unsolicited aid, information provoked merely by praising “When I Married Halldór Laxness” to Agnes Walsh. What came out had nothing to do with Laxness; it was about the courtship of the Sam B. to whom she dedicated the poem.

So the mild eroticism of “When I Married Halldór Laxness” owes as much to the person of Sam Bambrick as to anything in Laxness’s books. Maybe the birch billets do too, not being Icelandic. “Chunks of firewood in Newfoundland are junks, unless they happen to be birch junks, when they become billets” (Harold Horwood, quoted in Dictionary of Newfoundland English). Before the piece could be written, there had to be another marriage or merging of two affections: Sam Bambrick and Halldór Laxness. Whatever Laxness and his books contributed to the writing, Sam lent his attention, his body past its prime and perhaps a single Newfoundland word. Knowing this only confirms something unsurprising: the poem is an invention.

Another conversation with Agnes, this time about Laxness’ The Atom Station (which I read on her recommendation) produced another stray fact -- First Point is in Placentia. I intended to exhaust Laxness’ novels searching for First Point and was both relieved and disappointed when the location was handed to me. Never mind. Knowing it and knowing what to do with it are two different things. The first thing that comes to mind (besides more Newfoundland content) is the outrage to logic in the challenge to coordinate an actual place in one country with a fictional place in another. The poem/story is built on such wonderful outrages, so that’s nothing new. What is new is the thought, if we step away from the literal, that readers do leap easily from life to fiction, and do it all the time. Fixed in this country, we tour that one; from any actual place we travel widely in the realms of gold. Placentia, Newfoundland meets Glacier, Iceland, as Agnes Walsh meets Halldór Laxness (and Laxness meets Sam Bambrick), and they all mingle agreeably in a reader. I may have been on to something, suspecting that the piece is (indirectly) about reading, a homage to fiction so strong as to invade one’s very life. What more potent salute to life-changing writing than a writing-in-return that dissolves the boundary between life and literature, superimposing one on the other? I’m still asking, but I’ve thought my way around to a good question: is the meaning of the piece this delighted and delightful doubling -- as life and literature impossibly and decisively occupy the same dream?

(to be continued)

Friday, October 20, 2006

Hallowe'en Special - Dead Author Digital Downloads Half Price

DEAD AUTHOR DIGITAL DOWNLOADS

HALF ROTTEN - HALF PRICE!

between October 19 and November 1

only from www.rattlingbooks.com

Wilfred Grenfell (1865-1940) Adrift on an Ice Pan Digital Download Reg $9.95 Hallowe'en Special $4.95

Captain Bob Bartlett (1875-1946) The Last Voyage of the Karluk Digital Download Reg $19.95 Hallowe'en Special $9.95

Dillon Wallace (1863-1939) The Lure of the Labrador Wild Digital Download Reg $19.95 Hallowe'en Special $9.95

Monday, October 16, 2006

Icelandic Translation Contest

Inviting translations from English into Icelandic of a poem by Newfoundland writer Agnes Walsh entitled When I Married Halldór Laxness.

REWARD: The Winning Translator will be presented with a 4 Gig iPod preloaded with literature to listen to from Rattling Books, Walsh’s audio publisher (http://www.rattlingbooks.com/) and invited to read their translation in concert with poet Agnes Walsh and singer Anita Best at the Nordic House, Reykjavik, November 1, 2006.

SUBMISSION DEADLINE: October 25, 2006

SUBMISSIONS: Please send Submissions to the Writer’s Union of Iceland at the following email address by October 25, 2006:

rsi@rsi.is

In the body of the email provide your full name and telephone number.

For more information about Agnes Walsh and her interest in Iceland and Halldór Laxness check out Rattling Books Blog where there are several relevant posts.

http://www.rattlingbooks.blogspot.com/

FOR THE FULL TEXT OF THE POEM TO TRANSLATE GO TO THE LINK BELOW :

http://rattlingbooks.blogspot.com/2006/09/when-i-married-halldr-laxness-poem-by.html

Saturday, October 14, 2006

Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldór Laxness, Excerpt #3 from an essay by Stan Dragland

The following is the third in a series of excerpts from an essay by Stan Dragland (and conversation between Stan (SD) and Agnes Walsh (AW)) published in Brick 68 (Fall 2001).

Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldór Laxness (continued from October 6)

SD:

I was educated in the pseudo-science of close reading, Practical Criticism, to behave as though a text were a closed, autonomous signifying system. Put ’er in a bell jar and suck out the air. (I saw that done in the Oyen high school lab.) Everlasting flowers are better than real ones. How could it be an ivory tower when you don’t see any ivory?

The unfairness escalates. Shame on me for enjoying it.

But there's still something to be said for banishing most of the contextual whirlwind, if it’s eventually allowed to blow back in, preferably a zephyr at a time. I asked Agnes to write something about the genesis of “When I Married Halldór Laxness,” for example, but not before I´d given the poem a loosened form of close reading -- depending on my own resources to reach through technique towards the heart. I wanted to find out what I could say about it, more than any other poem in Agnes´s book, because it seemed so impervious to criticism. I was actually trying to keep the author at arm’s length, perhaps perversely feeling obliged to make it on my own but also convinced that she wouldn’t, maybe couldn’t, have my sort of relationship with her poem, that no more than I was she an authority on her own work. I know from experience the gap that opens between writer and writing when the latter estranges itself. “When I Married Halldór Laxness,” strange and dreamlike, seems clearly to have emerged from some such letting go.

But a shade of the Agnes Walsh I know was always near while I read and considered and wrote about her work. I had both to keep my independence from this wraith and write nothing that would dismay it. Like poetry, criticism has nothing to do with placation or flattery. It has nothing to do with ingratiation, with ego, neither hers nor mine. But an intense respect, a deep courtesy towards the writer at full stretch might stretch me taut in my turn. That benign presence at my elbow reminds me that her work and mine are phases of the same enterprise. Real people meet in flesh-and-blood writing. The creative and the critical, compatible and autonomous:

Reader, in your hand you hold

A silver case, a box of gold.

I have no door, however small,

unless you pierce my tender wall,

And there's no skill in healing then

Shall ever make me whole again.

Show pity, Reader, for my plight;

Let be, or else consume me quite.

The answer/title of this Jay Macpherson riddle/poem is “Egg,” but the address to a Reader elevated into proper noun makes Egg a metaphor for Book.

I write about dead authors just as tenderly as about those living -- tenderly and toughly -- tough it is to think in and then out, in my humanly limited way, into the heart of the work and on out through layer upon layer of meaning towards ... I wish I could drop that ellipsis. Untroubled participation in some continuum would sure be welcome. It’s a strange occupation, this heartfelt service of what I can neither name nor know.

AW:

Two subjects I have always been interested in are humor and eroticism. Two others are places (and especially islands), and what makes up the culture of places. When I was a young girl I had a stamp collection with stamps only from islands. Big land mass has never interested me: Canada, Australia, China, Russia. But the little dots have: the Faroes, Iceland, Tobago, Newfoundland, Ireland, etc.

I wrote this poem in the late 70s, not long after my father passed away. I was living at home then, having returned to be near my father in his old age. I had spent the ten years before that kicking around the U.S. and when I returned home I was struck by how much attention I was paying to detail, to small things in life, and to time passing. I spent a lot of time reading, a lot of time walking, thinking, imagining.

The atmosphere of the poem, the atmosphere I was living that is, was one of interest in light, wind, landscape, and observing. I believe that such a length of time in this “mind-frame” leaves one with pores more open and the mind “relaxed into a care-free sinking,” if I can quote myself from another poem.

While I was living this “atmospheric life” I was also going into St. John’s twice a month by out-of-town taxi to take books from the MUN library back out home with me. I read them the way I had collected stamps. Islands. I carted back out in Dominion bags books from islands. Halldór Laxness was one of them. Axel Sandemose was another (he is mentioned in the poem). Sandemose was from Denmark with a Norwegian mother, or perhaps it was the other way around. Sandemose had been in Newfoundland in the early part of the 20th century and wrote about his time here. So I stumbled upon his work also and read his truly amazing novel, The Werewolf. Then another, Horns for our Adornment. I remember the thrill I felt when I read in this novel: “The Fulton [a ship], was towed into St. John’s, it being impossible to force the narrow channel without a fair wind.” And later in the novel: “In Spain the climate was mild and people different. Here they were like they were in Norway. A disagreeable, everyday feeling of being at home. They spoke another language, but that was the only difference.” It thrilled me beyond words to read this in a novel. Growing up we never read about ourselves or our landscape in fiction. And that a writer I admired had been here, in fact was harboured here, supposedly in Fogo after he killed a ship-mate who was cruel to him. If any of you have seen the film Misery Harbour ... well that is Axel Sandemose’s novel and a loose version of his life.

So there I was reading Laxness and Sandemose at the same time, two great novelists. Laxness’ novel The Atom Station is about a young girl from the north of Iceland working as a house-maid in the city. The American military are at Keflavik wanting to set up an atomic tracking station. When I was growing up in Placentia, the American base in Argentia had flights, sailors going to Keflavik on an almost daily basis. All that seemed dream-like. I saw and heard the planes leave Argentia every day for Keflavik. I had no idea what the Americans were doing there but the sailors talked of it a lot. I only saw the streaks the planes left in the clear blue sky.

When I wrote the poem I was after reading these books by Laxness: World Light, The Happy Warriors, Christianity at Glacier, Salka Valka, and The Atom Station (the latter several times). I was also asking my parents a lot of questions about their past and events that happened before I was born. I had also met with my cousin Sam B., to whom the poem is dedicated. Sam is 20-25 years my senior, a bit of a traveler, and a social misfit. We hit it off and traded books. He courted me which pissed my mother off. She thought he was too old and a cousin to boot. I liked being courted by him because he could old-fashion waltz, was saucy yet respectful, and he had a wonderful musky smell. So you get my drift. I was reading Laxness, I was drawn to Sam. I was living the atmospheric life of Nordic fiction, forbidden passion, and old Newfoundland, all mixed together with writing.

For me it is an erotic poem. A literary, folkloric, dream-state fantasy of living on the edge of the earth.

When I Married Halldór Laxness (from In the Old Country of My Heart)

(for Sam B.)

I watched the froth go down and the yellow liquid rise to meet it. I twisted the glass around and it tipped over and spilled on his arthritic knee. I looked to the side and didn’t apologize. His beautiful bony fingers flicked off the foam in separate particles as if it was incidental lint he had finally noticed.

The decision is yours now.

He rubbed the liquid into his pant leg. I sighed. Either decision I make will kill something.

And so, you want to hang in this ether land forever?

Yes.

And if I pulled your hair?

And if I scalded your mouth?

And if I made a teepee of birch billets with you in the centre?

Look at me.

No.

He went away.

Next night the phone rang.

I’ll meet you at Glacier and First Point. You must be exact.

I’ll be there for three evenings.

For three nights I wore myself ragged but couldn’t find where.

Friday evening the doorbell rang. He handed me two books by Aksel Sandemose. I put my fingers exactly where his warm fingerprints still lingered on the top book and closed the door. I read and waited.

(There was a tidal wave and a woman went from window to window with a candle in her hand as her house floated out the bay. They rescued her in St. Lawrence.)

When you are ready, if ever, light your own candle.

Two years later, my hand shook as I held the match. His hair had greyed around the temples and he crippled shyly.

Five years later, two babies look hauntingly like him. He is chopping wood in the backyard. He stops.

Look at me. I fooled you years ago. Glacier is in Iceland and I tore out all the pages where it was written in that book. Do you regret that we called the babies Abstract and Zero? Come feel Aunt Hilda and Didymus under my fingernails.

His gentle laugh ripped the night sky, and I got pregnant again.

(to be continued)

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

Antonia Sula May Francis: Earphones Award winning Narrator

This is a photo of Antonia a few years ago. I'm her Mom.

I used to produce a weekly one hour radio program with Rachel Bryant for the Alder Institute. It was called Open Air: Natural History Radio from Newfoundland and Labrador. We did that for four years.

Natural History we defined as everything. Not to limit ourselves and the fun we could have. Like having Andy Jones telling Jack stories and riding a tandem bike around old Havana or watching fledging murre chicks tripping over my microphone on their way to life at sea.

When Antonia was five she performed a Christmas story for Open Air's Christmas program. The True Meaning of Crumbfest by David Weale. She did it like a five year old which is to say no one you know who is not a five year old could have done a better job. Which is why now that her Mom is an audio publisher and Antonia's narration is an audio book, Antonia Sula May Russell Francis is an Earphones Award winning narrator.

Monday, October 09, 2006

Author Guest Blog – Susan Rendell

This is the first in a series of occasional Guest Blogs from Authors published in audio by Rattling Books.

Susan Rendell is the Author of In the Chambers of the Sea, a collection of short fiction originally published by Killick Press in 2003. Rattling Books released an unabridged audio edition of In the Chambers of the Sea in 2004, narrated by Anita Best, Deirdre Gillard-Rowlings, Joel Hynes, Susan Rendell, Janet Russell, Janis Spence, Francesca Swann and Agnes Walsh.

Author Guest Blog – Susan Rendell

Janet Russell, my beloved publisher, has asked me to write something about characters for her new blog. So, characters.

Well, the way it goes with me is that they just show up on their own, usually with names and other stuff – pets, allergies - homicidal impulses – no, wait, those are Ken Harvey’s characters – mothers, fathers, kids – and if I’m lucky, designer shoe fetishes (in which case I get to put down Manolo Blahnik a bunch of times, and fantasize). And then they get involved in stuff over which I have no control - I listen and watch and type as fast as I can, stretch and strain after dialogue and images that waver and go out if, for instance, my daughter comes in and says, “Where’s the umbrella?” (The customary reply is, “You know where the umbrella is, you spawn of Satan, you’re just trying to kill your mother, you. . .” – at which point the door usually closes quickly and firmly. She doesn’t come back until the next line that’s going to propel me firmly in the direction of a magnum opus or Magna Carta or at least a contract is dancing just out of my reach, and I’m reeling it in and it’s coming, it’s coming, yes!, and – “Has the dog been fed?” To which the customary reply is “I am going to kill you and the dog and the neighbour’s dog and the cat up the street who looks like a dog. . . Slam.)

Sometimes I use real people as characters, but they are so cleverly disguised I would never get grabbed by the real person at, say, a big fancy reception where the booze and the food are flowing freely and I’m wearing a new dress and feeling pretty cool in my knock-off Blahniks, when suddenly a hand comes out of the crowd and grabs me hard around the wrist and a voice dripping with menace says, “You put me in your book,” and I can feel all the hairs on my body standing to attention, even the ghosts of plucked and shaven hairs, and then. . .but this never happens, as I said, because of the clever disguising, etc. It might have happened to a friend once, though.

Speaking of characters, there are some in the excerpt from the novel I’m working on. I thought one of them might be my great aunt, owing to certain similarities in era, pursuits, etc., but my aunt never murdered anyone and stuck the body in a well - as far as I know - as this person seems bent on doing unless one of the other characters stops her. I have no faith in any of them that way, their collective intelligence or moral fibre - indeed I’m not even sure how they manage to button their boots in the morning – so it’s likely there will end up being a body in the well. I just hope it doesn’t turn out to be the dog’s, because he does have a few redeeming qualities – he never kills or even chases chickens, for instance, even though his mother was murdered by one.

Susan Rendell is the Author of In the Chambers of the Sea, a collection of short fiction originally published by Killick Press in 2003. Rattling Books released an unabridged audio edition of In the Chambers of the Sea in 2004, narrated by Anita Best, Deirdre Gillard-Rowlings, Joel Hynes, Susan Rendell, Janet Russell, Janis Spence, Francesca Swann and Agnes Walsh.

Author Guest Blog – Susan Rendell

Janet Russell, my beloved publisher, has asked me to write something about characters for her new blog. So, characters.

Well, the way it goes with me is that they just show up on their own, usually with names and other stuff – pets, allergies - homicidal impulses – no, wait, those are Ken Harvey’s characters – mothers, fathers, kids – and if I’m lucky, designer shoe fetishes (in which case I get to put down Manolo Blahnik a bunch of times, and fantasize). And then they get involved in stuff over which I have no control - I listen and watch and type as fast as I can, stretch and strain after dialogue and images that waver and go out if, for instance, my daughter comes in and says, “Where’s the umbrella?” (The customary reply is, “You know where the umbrella is, you spawn of Satan, you’re just trying to kill your mother, you. . .” – at which point the door usually closes quickly and firmly. She doesn’t come back until the next line that’s going to propel me firmly in the direction of a magnum opus or Magna Carta or at least a contract is dancing just out of my reach, and I’m reeling it in and it’s coming, it’s coming, yes!, and – “Has the dog been fed?” To which the customary reply is “I am going to kill you and the dog and the neighbour’s dog and the cat up the street who looks like a dog. . . Slam.)

Sometimes I use real people as characters, but they are so cleverly disguised I would never get grabbed by the real person at, say, a big fancy reception where the booze and the food are flowing freely and I’m wearing a new dress and feeling pretty cool in my knock-off Blahniks, when suddenly a hand comes out of the crowd and grabs me hard around the wrist and a voice dripping with menace says, “You put me in your book,” and I can feel all the hairs on my body standing to attention, even the ghosts of plucked and shaven hairs, and then. . .but this never happens, as I said, because of the clever disguising, etc. It might have happened to a friend once, though.

Speaking of characters, there are some in the excerpt from the novel I’m working on. I thought one of them might be my great aunt, owing to certain similarities in era, pursuits, etc., but my aunt never murdered anyone and stuck the body in a well - as far as I know - as this person seems bent on doing unless one of the other characters stops her. I have no faith in any of them that way, their collective intelligence or moral fibre - indeed I’m not even sure how they manage to button their boots in the morning – so it’s likely there will end up being a body in the well. I just hope it doesn’t turn out to be the dog’s, because he does have a few redeeming qualities – he never kills or even chases chickens, for instance, even though his mother was murdered by one.

Friday, October 06, 2006

Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldór Laxness, Excerpt #2 from an essay by Stan Dragland

The following is the second in a series of excerpts from an essay by Stan Dragland (and conversation between Stan (SD) and Agnes Walsh (AW)) published in Brick 68 (Fall 2001).

Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldór Laxness (continued from October 3)

SD:

I met my first Icelander in Alberta, on the Orthopaedic ward of the University Hospital in Edmonton while I was a relief orderly in the summer of 1963. He had hurt his back badly and had to spend the days stretched out on a Stryker Frame. A big man for that narrow, rigid rig. Did he have to sleep on it? He was not allowed to turn on his own, so at regular intervals the nurse and I would make an Icelander sandwich by lowering the top (or bottom) of the frame onto him, securing it, strapping him in and then, Ready? On three. One, two, THREE, we’d spin him 180 degrees to his stomach (or back), then remove the bottom (or top) and there he’d be, still flat but with gravity pulling at a different side of him. I admired Mr Stryker’s invention and I greatly enjoyed flipping the Icelander.

I’m telling this to Agnes and Marnie in the kitchen of the Fitzpatrick Street house in St. John’s. How has it come up? I can’t recall it ever coming up between 1963 and now, 1997. Something in the conversation released the Icelander and my conversation with him about Halldór Laxness’s Independent People, my only contact with anything Icelandic up to 1963. Yes, he certainly had read the novel and he was mildly surprised that I had.

He might have been more surprised had he known how accidentally I came to the book. Laxness was not unknown in 1963. He had won the Nobel Prize in 1955, after all, “a remarkable and exceptional achievement,” according to his translator, “for an author writing in a minority language in the smallest, youngest nation in the western world.” This is forgetting the ancient sagas that Laxness folds into his novels, but what did I know of such things in high school? I happened on this most famous novel of Iceland in the Oyen High School library, a random collection without any sense to it and the town’s only library when I was a student in the late 1950s. There was a bigger library in my office when I retired from teaching. I read all the fiction in the high school library -- everything except The Golden Dog. Out of all those shabby hardcovers, only Independent People stayed with me, that and Les Misérables in the fancy Val Jean edition. Years later, when I bought the whole edition in a used bookstore, what was I looking for? The years before order when I moved from book to book like water seeking its own level?

The hard, hard life of Bjartur of Summerhouses in Independent People, bleaker even than the lives of the Andrews and Vincent families in Bernice Morgan’s Newfoundland novels -- whatever Agnes said to recall this epic struggle of a nobody is lost in the story of her own fascination with Halldór Laxness that she told us at the kitchen table. I had the feeling the story was surprised out of her. I could tell she was inside her life, not outside watching for anecdotes to dine out on. “We neither of us perform for strangers,” says Miss Elizabeth Bennett to Mr Darcy in Pride and Prejudice. Talk and not silence greases the gears of the world, but I don’t talk, not freely, and I’m drawn to other stoneboats of speech: heavy, hard to get moving.

In Alberta, for me, Iceland was frozen in its name. Now, in Newfoundland, the name begins to melt as I discover that the whole country is heated by thermal springs, though a cup of coffee in Reykjavík costs $5.00 Canadian -- no wonder Icelanders charter planes to shop in Halifax and St. John’s at stores displaying those Velkominn signs -- and that they won their fish wars while we lost ours.

Loving Halldór Laxness’s writing, especially The Atom Station, Agnes decided one day in 1989 to call Mr. Laxness up. Newfoundland to Iceland, long distance, yes, but a thinkable distance, not like Alberta to Iceland in the late 1950s -- though Iceland was then in one way more real to me than my own province: I’d never read about Alberta in a book.

How to reach Mr. Laxness without a number? Call information. Let’s see, 011, 354

and then 0 for the Reykjavík operator.

I’m trying to reach Mr. Halldór Laxness please.

Ah, Mr. Laxness. Mr. Laxness has three numbers. There is his house, his office, and his

country house. That is where Mr. Laxness is at the moment, at his country house. But I

regret to say that this is not an opportune time to call. At the moment Mr. Laxness is

not well.

Is it serious?

No, an indisposition. But he is not taking calls.

Well then, thank you very much.

The life that sings, the rich green slope of the irony in Halldór Laxness’s books, sprouted a need in Agnes to find out how the man was but not to make herself known to him. She never spoke to him, not that day nor any other. It wasn’t necessary. She had a satisfying semi-annual Laxness conversation with various Reykjavík operators for most of a decade, though it had been a few years since the last call when we talked in the Fitzpatrick Street house in 1997, the year before Halldór Laxness died.

AW (e-mail response to -- diplomatic correction of -- the above):

Hi Stan, I’m taking your piece and I’m playing around with it. Not because there’s anything wrong with it but because it got me interested in thinking back over it all again. Here goes a bit of fun. It’s just my own fun. It does not mean that I think you should change a thing. I dial the info operator number and a woman answers in what I assume is Icelandic but it sounds a bit like English too. I say I am looking for a phone number for a Mr. Halldór Laxness, a writer from there who probably lives in Reykjavík or has an office number at the university. She cuts me off with yes, yes, of course Mr. Laxness, but he isn’t at the university any longer. He has retired, he is an old man. Oh, I say, surprised at the stream of information, is he well known then in Iceland, I ask. Well, yes, of course, everyone knows him here, she tells me. I see, I say. I didn’t know at the time that everyone in Iceland reads everything. Perhaps I’ll take his home phone number then, I say. All right, hold a moment, I have it right here ... ah, but that’s right, she says, he isn’t home now, he’s in Bangkok at a world peace conference. But I’ll give you his number and you can try him next week. I took it knowing I would never call. Six months later I dial the Icelandic info operator again and ask for his phone number, although I haven’t lost it. The operator gives it to me. I ask if he is in the country. Yes, she says, she thinks so. I ask how old Mr. Laxness is, if she knows. She pauses, says, let me see, one moment. I hear her speak in Icelandic. I hear several voices with questioning intonations. She comes back and says, we think eighty-five. Ah, I say, and do you know if his health is ok. Oh yes, she assures me, he is very active, travels a lot. Good I say. I tell her I am calling from Newfoundland and that he is a favorite writer of mine. I ask if she likes his work. Oh yes, he is an important writer for the Icelandic people. Yes, I say and I thank her. I called back about twice a year for some years to check on him. I used to imagine the operators would check in on him after their shift. Probably discuss something in one of his novels, but that was taking it too far. When I read a few years ago that he had passed away I couldn’t help but think about the operators.

Love, Ag

Mother of Pearl: Agnes Walsh and Halldór Laxness (continued from October 3)

SD:

I met my first Icelander in Alberta, on the Orthopaedic ward of the University Hospital in Edmonton while I was a relief orderly in the summer of 1963. He had hurt his back badly and had to spend the days stretched out on a Stryker Frame. A big man for that narrow, rigid rig. Did he have to sleep on it? He was not allowed to turn on his own, so at regular intervals the nurse and I would make an Icelander sandwich by lowering the top (or bottom) of the frame onto him, securing it, strapping him in and then, Ready? On three. One, two, THREE, we’d spin him 180 degrees to his stomach (or back), then remove the bottom (or top) and there he’d be, still flat but with gravity pulling at a different side of him. I admired Mr Stryker’s invention and I greatly enjoyed flipping the Icelander.

I’m telling this to Agnes and Marnie in the kitchen of the Fitzpatrick Street house in St. John’s. How has it come up? I can’t recall it ever coming up between 1963 and now, 1997. Something in the conversation released the Icelander and my conversation with him about Halldór Laxness’s Independent People, my only contact with anything Icelandic up to 1963. Yes, he certainly had read the novel and he was mildly surprised that I had.

He might have been more surprised had he known how accidentally I came to the book. Laxness was not unknown in 1963. He had won the Nobel Prize in 1955, after all, “a remarkable and exceptional achievement,” according to his translator, “for an author writing in a minority language in the smallest, youngest nation in the western world.” This is forgetting the ancient sagas that Laxness folds into his novels, but what did I know of such things in high school? I happened on this most famous novel of Iceland in the Oyen High School library, a random collection without any sense to it and the town’s only library when I was a student in the late 1950s. There was a bigger library in my office when I retired from teaching. I read all the fiction in the high school library -- everything except The Golden Dog. Out of all those shabby hardcovers, only Independent People stayed with me, that and Les Misérables in the fancy Val Jean edition. Years later, when I bought the whole edition in a used bookstore, what was I looking for? The years before order when I moved from book to book like water seeking its own level?

The hard, hard life of Bjartur of Summerhouses in Independent People, bleaker even than the lives of the Andrews and Vincent families in Bernice Morgan’s Newfoundland novels -- whatever Agnes said to recall this epic struggle of a nobody is lost in the story of her own fascination with Halldór Laxness that she told us at the kitchen table. I had the feeling the story was surprised out of her. I could tell she was inside her life, not outside watching for anecdotes to dine out on. “We neither of us perform for strangers,” says Miss Elizabeth Bennett to Mr Darcy in Pride and Prejudice. Talk and not silence greases the gears of the world, but I don’t talk, not freely, and I’m drawn to other stoneboats of speech: heavy, hard to get moving.

In Alberta, for me, Iceland was frozen in its name. Now, in Newfoundland, the name begins to melt as I discover that the whole country is heated by thermal springs, though a cup of coffee in Reykjavík costs $5.00 Canadian -- no wonder Icelanders charter planes to shop in Halifax and St. John’s at stores displaying those Velkominn signs -- and that they won their fish wars while we lost ours.

Loving Halldór Laxness’s writing, especially The Atom Station, Agnes decided one day in 1989 to call Mr. Laxness up. Newfoundland to Iceland, long distance, yes, but a thinkable distance, not like Alberta to Iceland in the late 1950s -- though Iceland was then in one way more real to me than my own province: I’d never read about Alberta in a book.

How to reach Mr. Laxness without a number? Call information. Let’s see, 011, 354

and then 0 for the Reykjavík operator.

I’m trying to reach Mr. Halldór Laxness please.

Ah, Mr. Laxness. Mr. Laxness has three numbers. There is his house, his office, and his

country house. That is where Mr. Laxness is at the moment, at his country house. But I

regret to say that this is not an opportune time to call. At the moment Mr. Laxness is

not well.

Is it serious?

No, an indisposition. But he is not taking calls.

Well then, thank you very much.

The life that sings, the rich green slope of the irony in Halldór Laxness’s books, sprouted a need in Agnes to find out how the man was but not to make herself known to him. She never spoke to him, not that day nor any other. It wasn’t necessary. She had a satisfying semi-annual Laxness conversation with various Reykjavík operators for most of a decade, though it had been a few years since the last call when we talked in the Fitzpatrick Street house in 1997, the year before Halldór Laxness died.

AW (e-mail response to -- diplomatic correction of -- the above):